The Sacramento City Unified School District is changing how it approaches student discipline, joining a growing number of districts adopting a “restorative justice” approach aimed at reducing suspensions of black and Hispanic students.

The Sacramento City Unified School District (SCUSD) is changing how it approaches student discipline, joining a growing number of districts adopting a “restorative justice” approach aimed at reducing too many suspensions of black and Hispanic students.

Alex Barrios, spokesman for the California district, told the News Review officials are focusing on keeping misbehaving students in school by directing them to mediated talking sessions or other counseling, rather than sending them home or isolating them with in-school suspension. One of the most perverse outcomes of suspensions is that students who are suspended miss valuable instruction time in the classroom which undermines their ability to achieve successful results on course examinations.

Barrios said the new approach is intended to “ensure that our system is more focused on helping students understand how their actions impact others and holding them accountable for those actions, rather than punishing them.”

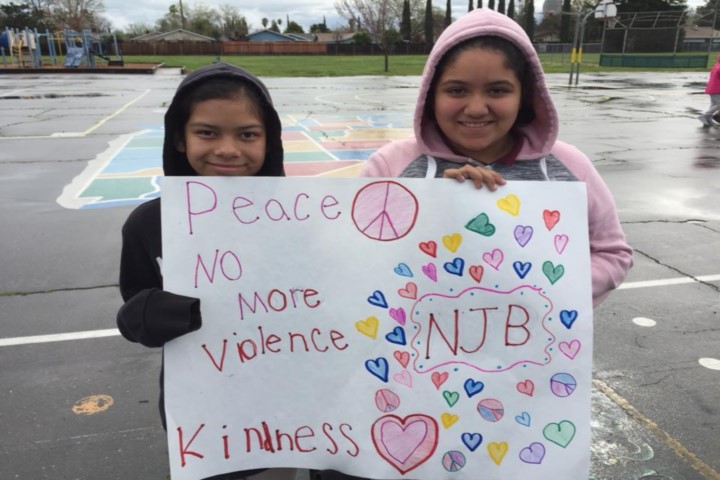

The idea is to confront student discipline issues through talking sessions designed to better understand the life circumstances, such as poverty or trauma, that may contribute to bad behavior. The Sacramento district created an Equity Office and launched a SPARK program – social emotional learning, positive relationships, analysis of data, restorative practices, and kindness – to train teachers in restorative justice techniques. Restorative justice, although not a punishment, does not let wrongdoers off the hook.

The new approach is energizing some teachers, while others are concerned about a lack of support for educators to implement the restorative justice measures.

“I’ve been in SCUSD for 20 years, and it’s the same speech,” one participant in the district’s 2016 SPARK conference told the News Review. “I understand there is implicit bias. I want to help my students, but the conversation never goes beyond that fact that implicit bias exists. What specific things can my school do to include and support all of our students? The first step is being aware that there is a problem, but then what? The workshops never get past the first step.”

Wood believes restorative justice programs work well for students involved from an early age, but not as well for students who came up through traditional disciplinary programs. To help with the transition, Wood suggests schools install video cameras in classrooms to help teachers perfect their restorative justice techniques.

“Teachers need game film, and they need to be able to have an understanding of what they’re doing better,” he said. “This doesn’t mean they’re bad people. But good people can still do harmful things.”

James Davison Hunter, founder of the Institute for Advanced Studies in Culture, identifies the importance of cultivating a shared vision of morality to instill strong character virtues in students when he writes in “The Tragedy of Moral Education in America”:

(The) components of morality are expressed in a community’s institutions, including its moral rules. It is a shared understanding of the world by which a community knows what is right and wrong, what is normal and abnormal, what is possible and not possible, how to distinguish the good person from the bad. When it functions well, our moral culture binds us, compels us, obliges us, in ways of which we are not fully aware.

Moving away from punitive systems of discipline is hard work culturally. It takes time to reshape the assumptions of teachers and students alike, and failure to lead that cultural transformation will produce frustration. The State of Illinois offers a guide to implementing restorative justice. For school systems that are going to take the long road to restorative practices, it is worth investigating the time and energy to do it well.