When 10-year-old Tirhas Hagos moved to Tucson, Arizona from Ethiopia with her family two years ago, she didn’t know English.

When 10-year-old Tirhas Hagos moved to Tucson, Arizona from Ethiopia with her family two years ago, she didn’t know English.

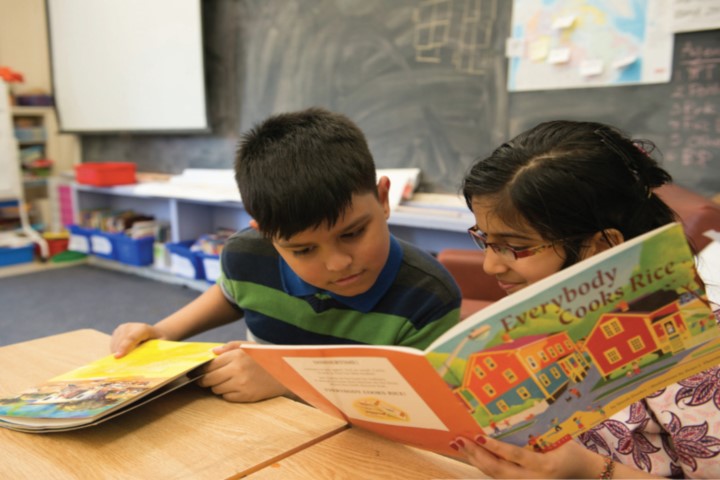

Today, the fourth-grader receives high marks for literacy, including fluency and comprehension, thanks in large part to volunteers with the Senior Corps Foster Grandparents program.

Reading mastery is usually completed by the second grade. Social scientists have long recognized that few variables are more determinative of juvenile deliquesce later in life than the inability to read. By addressing this core academic skill within an identified at risk student population, these grandparents have made a major contribution to their community. Moreover, there is almost no substitute for the concrete care and example of a teacher or adult in a student’s life. Researchers at the Institute for Advanced Studies in Culture that study moral development observed, “The moral example of teachers and other adults unquestionably complemented the formal instruction students received, it was far more poignant to, and influential upon, the students themselves.”

The Foster Grandparents, a program funded by the federal Corporation for National and Community Service, partners volunteers over the age of 55 with teachers for 15 to 40 hours per week to help students struggling with reading, the Arizona Daily Star reports.

“I love my work,” said Susan Mason, a former executive assistant at Raytheon Missile Systems who now works three days per week as a literacy tutor at John B. Wright Elementary School. “I feel fantastic when they get it. They have trouble with comprehension, but when they understand what they are reading, it is the best feeling in the world.”

With word search puzzles, and playing games like Old Maid, Go Fish and Uno, Mason helps students build their vocabulary and rewards them with stickers to decorate their folders. Students work through books about UFOs, and firewalkers on the island of Bora Bora, and discuss the stories afterward to ensure they understand the words.

“These students are amazing,” Mason said. “Many speak three languages.”

Wright Principal Deanna Campos said the Foster Grandparents program is making a significant impact at the school, where about half of the pre-school through fifth grade students are refugees. Despite the language barrier faced by many of them – Wright’s refugee students represent 22 different cultures and languages – the school scored a B-plus on standardized tests.

“They go every day and read to an adult without anyone judging them,” Campos said. “The students are learning English, and when they read with Susan, they develop the fluency they need to be successful readers.”

Mason is among about 30 volunteers who work for the Senior Corps Foster Grandparents in the Tucson area, including at schools in the Flowing Wells, Tucson, Sunnyside and Marana districts. In Arizona, the program is sponsored by Northern Arizona University’s Civic Service Institute, and operates on a budget of about $750,000 a year.

The funding covers a small staff, as well as a small stipend and mileage, fingerprinting and background checks, for roughly 100 volunteers statewide.

Teachers and principals working to strengthen moral and citizenship formation in their students will find information, strategies and lesson plans at the UK’s The Jubilee Centre.