I found a new me and began a new life

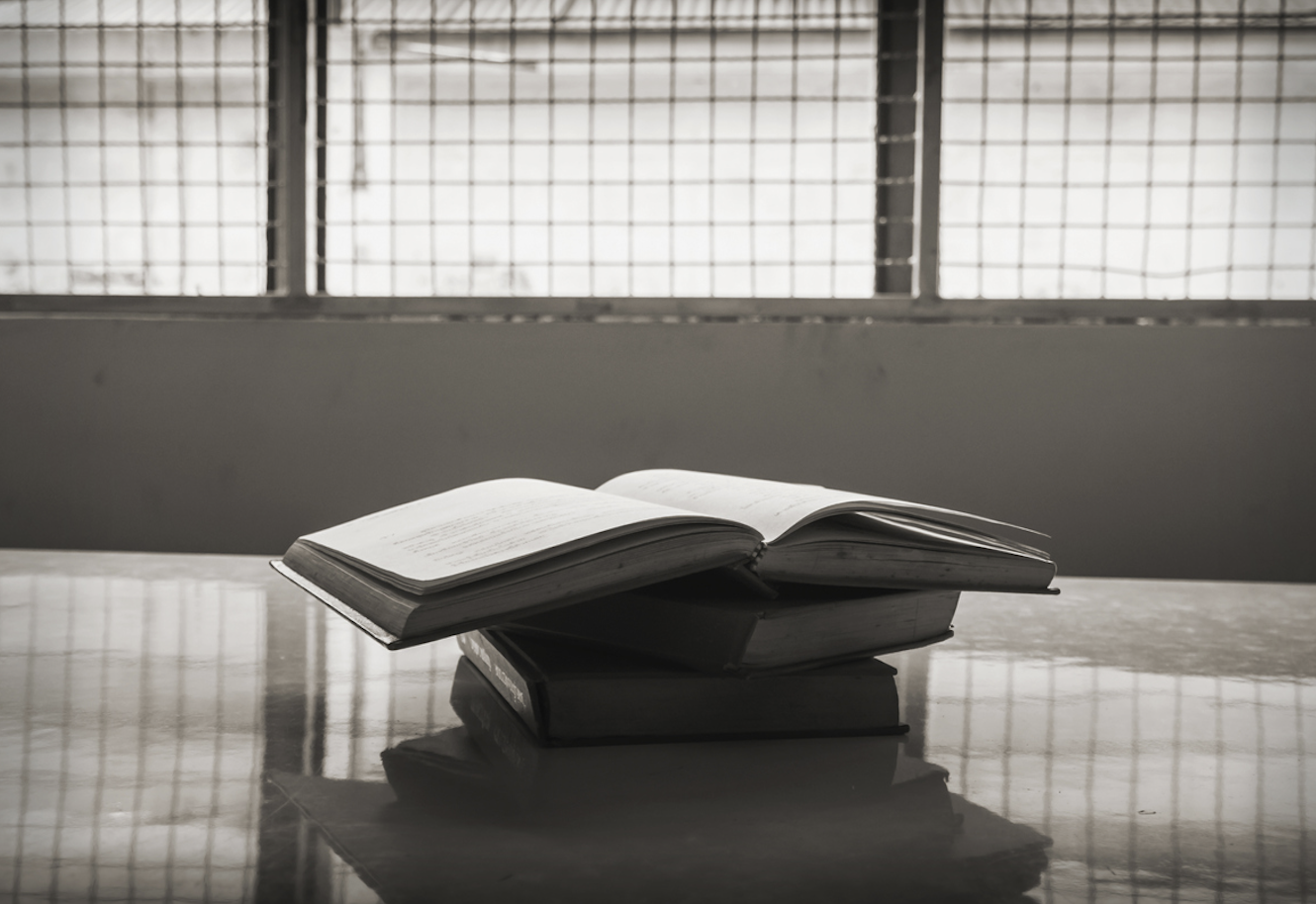

I was 18 years old and had been incarcerated at Beaumont Juvenile Correctional Center in Virginia for four years when, in the spring of 2016, a very unorthodox educational opportunity became available to me and my peers: a University of Virginia (UVA) program called Books Behind Bars. This is a class conducted by Professor Andrew Kaufman, in which his UVA students travelled to Beaumont once a week to discuss Russian literature. We were divided into eight groups sitting at eight different tables. At each table UVA, students and offenders discussed the works of Leo Tolstoy, Fyodor Dostoyevsky, and other Russian authors.

Initially, I suspected that things would have been awkward and tense by taking people from polar opposite backgrounds and integrating them into a vulnerable environment. I was abrasive and thought that it was not for me. My colleagues and peers encouraged me to give it a chance. I recall in particular one story we read by Leo Tolstoy called “How Much Land Does a Man Need?” In this story the protagonist ends up losing everything including his life because of his greed. “Six feet from head to toe was all he needed,” Tolstoy writes at the end. We all had different viewpoints on Tolstoy’s answer to the question in the story’s title. By the end of the conversation, I realized that my own beliefs could be changed by openly listening to those of others.

As the weeks carried on, the UVA students and I began to get to know each other through the stories we were discussing. After breaking down the literature and exchanging thoughts and feelings about the stories, we began to communicate on a level that was previously non-existent for us all. I realized I could be vulnerable, change my mind, and even admit to not being certain about my answer, without being judged by the others.

Not only was I learning about the individuals at my table, but I was also learning about myself, discovering views, beliefs, and feelings. During one conversation, about a story called “My First Tooth” by Varlam Shalamov, I learned that I was much more forgiving than I thought I was. Just like the narrator of the story had forgiven the prison guard who had once mistreated him, I suddenly realized that I was now finally able to forgive my step-brother for the role he played in my incarceration. I discovered the role literature and conversation could play in my own transformation.

While at that table, I discovered part of my identity. I realized that my social identity was not as blemished as I thought it was. I learned that my university peers, in completely different life situations, shared the same problems as me, and they too were trying to become better people. As strange as it may sound, it was as if, during those ninety-minute conversations each week, I was free while incarcerated. I was mentally freed from that institutional, systematic oppressing narrative that ruled my life at the time. While inside those classroom doors sitting at the tables with my UVA partners, I was the only person I had never been before: myself.

I started to notice that the impact of the class was reaching outside of those metaphorical prison gates. For example, my communication was greatly improved. My mother and I didn’t have the greatest connection. One day after the Books Behind Bars class I started an open discussion with her and we started to communicate differently, with the purpose of learning about one another. We talked about why we were not very close emotionally. We talked about her childhood and how it affected the manner in which she expressed love and care. A very overdue connection was initiated between the two of us.

The lessons I was learning from those discussions about Russian literature were something I started implementing in most of all of my communications. It was if I was meeting everyone I previously knew all over again. I was now able to communicate openly about uncomfortable topics.

As the Russian literature class came to an end, it was very bittersweet. Although we had to go, we were leaving with so much more than we came in with. It was then that I discovered the power of true education. It can change your mind set about who you are as a person and can change how you relate to others. From then on, I took my education as seriously as the Sahara takes rain, and enrolled in every educational program available.

I am now 24 years old and have been released for over a year. The impact that the Books Behind Bars class had on my identity still exists today. I can see how effectively I communicate in personal and business conversations. I notice it in my relationships with family and friends. I truly believe that I would not be the person I am today, nor have obtained the level of success that I have, if I would have never enrolled in that unusual Russian literature class in the spring of 2016. It opened a door to opportunity, and when I walked through that door, I found a new me and began a new life.

—

Brad Brewer is a former student in the Books Behind Bars program that is founded by UVA Professor Andrew D. Kaufman. Add this link: https://andrewdkaufman.com/about-books-behind-bars/