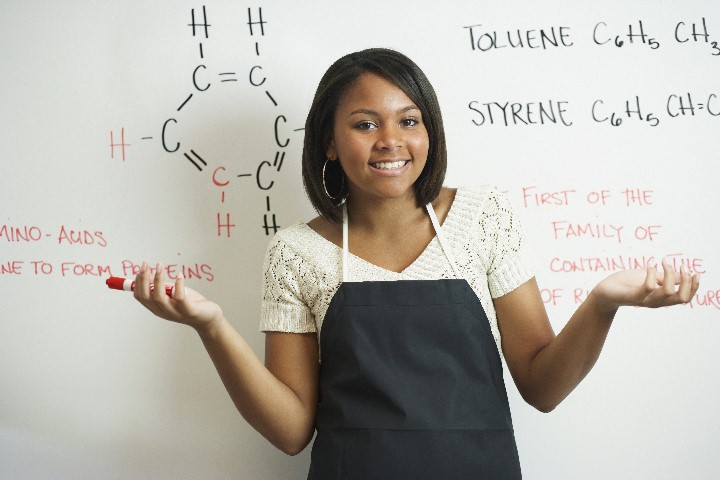

Destiny, a junior at Springfield Renaissance School, stands at the whiteboard in her math class and tells her classmates, "I'm not sure if this is right." Admitting such vulnerability, especially as a high school junior, takes courage.

Destiny, a junior at Springfield Renaissance School, stands at the whiteboard in her math class and tells her classmates, “I’m not sure if this is right.” Admitting such vulnerability, especially as a high school junior, takes courage. Destiny is lucky that her school is forging ahead to try and intentionally form courage in all the members of its community, teachers, and students alike.

Ron Berger, chief academic officer of EL Education, which partners with Springfield, described the approach that EL partner schools take to cultivating “differentiated courage.”

It’s a natural reaction to walk into a successful school, such as Springfield, and wonder what the “secret sauce” is to get 98% of your students graduating on time and 100% of graduates accepted into college. Berger’s answer is, “many things. But one of the most important factors is academic courage.”

Berger explains that EL Schools have an understanding of courage, what they call “differentiated courage,” that they think helps students intuitively connect with the concept and apply it to their own lives. For instance, some people show courage through their service in the armed forces, and others exemplify it by taking the stage in front of an audience. Berger clarifies, “We all have courage in certain realms and less in others. And we can all work on our courage where we need it.”

Berger has seen this understanding and approach to building courage have an impact across EL’s schools. Students begin to see that school provides a breadth of opportunities to display courage, “science courage . . . art courage, or their Shakespeare courage.”

Berger elaborates on the specific case of Destiny and calculus courage, “It means you don’t hide in calculus class, pretending you understand things when you don’t, or pretending you’re too cool to care about the work. It means you take the risk to raise your hand and ask questions, to share your thinking with others, to take critique from peers.”

While some critics might argue that it’s questionable whether or not courage is a virtue that can be formed, Berger says it one hundred percent can be and it should be. He says, “Cultivating courage in students must start with teachers. In fact, the best way for students to learn it is for teachers to model it.”

In EL Schools, teachers lead by admitting their own learning struggles, and then the class courageously works together to master bodies of knowledge that still perplex them. In this way, teachers can not only teach the content but model the virtues of humility and courage that their students will need to take the same learning journey.

Courage and humility are not formed in social isolation. Children need role models to orient themselves to when they are in the initial stages of understanding a virtue like courage. Institute for Advanced Studies in Culture founder James Davison Hunter explains in The Death of Character, “Character is not . . . solitary, autonomous, unconstrained; merely a set of traits within a unique and unencumbered personality. Character is very much social in its constitution. It is inseparable from the culture within which it is found and formed.”

The Renaissance School shapes culture by beginning with teachers, and the students learn by practice. There is hardly a better recipe for learning.

EL Schools offers recommendations for building a culture of grappling to help educators build courage in themselves and in their students, whether for calculus or public speaking or essay-writing.