The German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900) predicted a day when it would be impossible to say, “Thou shalt not.” In late-modern North America, we are fast approaching that day. To the degree that this is true, it will influence how we think about and engage in character formation.

To fully appreciate what Nietzsche anticipated, we will need to know what character is, how it is formed, and what assumptions about the nature of the human person are involved.

Traditionally, character is composed of discipline, attachment, and autonomy: the inner capacity for restraint, an alignment with values and aspirations of a larger community, and the capacity to freely make ethical decisions.

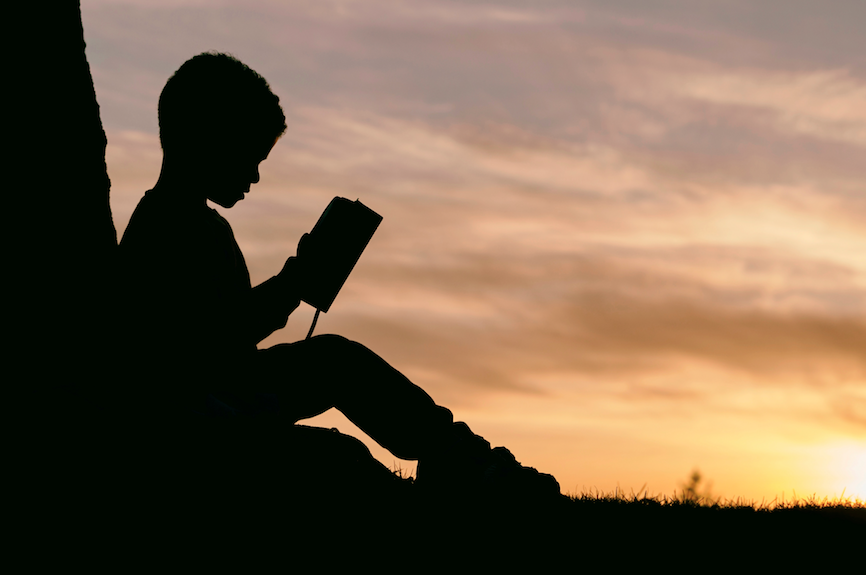

This traditional definition, however, is largely dependent on one’s anthropology. Traditionally, the child was seen as underdeveloped and thus dependent on others for moral formation. It was thought that humans are not born with a well-developed moral sensibility, much less anything approaching “character.” As a consequence, moral formation has always been seen as an essential part of parenting and schooling.

However, over the last century, this anthropological understanding of the child has been abandoned. Today the child is seen as inherently good and capable of self-deriving their own moral perspectives. The process of moral formation has thus shifted from restraint to permission. Moral education is about getting out of the child’s way in order to enable the child to express their inherent moral capabilities. Much of the debate has been in how one best gets out of the way. In this manner, the entire moral education enterprise has been turned on its head.

Rather than discussions of given moral creeds and communities of engagement, we encourage the individual child unencumbered by historic or community standards to simply express his or her values. The locus of authority for morality has shifted from outside to inside: from virtues to values, from community standards and traditions to the autonomous self.

Since society’s moral institutions in this new understanding have no essential role, they have been weakened or encouraged to abandon their formative role. The best that they can do is simply get out of the way of the child.

All of this pivots then on whether we have an accurate assessment of human nature. The anthropological basis of moral formation is foundational.

If character formation is understood in its traditional understanding, we’d have to conclude that this new understanding of moral education renders character dead. This situation demands plain speaking. We want character without unyielding convictions; strong morality without the burden of guilt; virtue without moral justifications that offend; the good without

having to name evil; community without limitations on personal freedom. We want the benefits of moral formation without any effort at or responsibility for moral formation.

Thus the entire enterprise of moral education pivots on one’s foundational understanding of the nature of the child. We cannot restore character without first asking whether we have adopted an accurate assessment of human nature. The contemporary approach to moral education is an inversion of past approaches. We have abandoned pedagogies of restraint in favor of pedagogies of permission. These are two diametrically opposed frames. All analysis of moral education needs to start by acknowledging this shift and these two frames