A Maine nonprofit is taking a new approach to education in three rural Washington County schools where many students struggle with adverse childhood experiences—problems often tied to poverty that hinder learning.

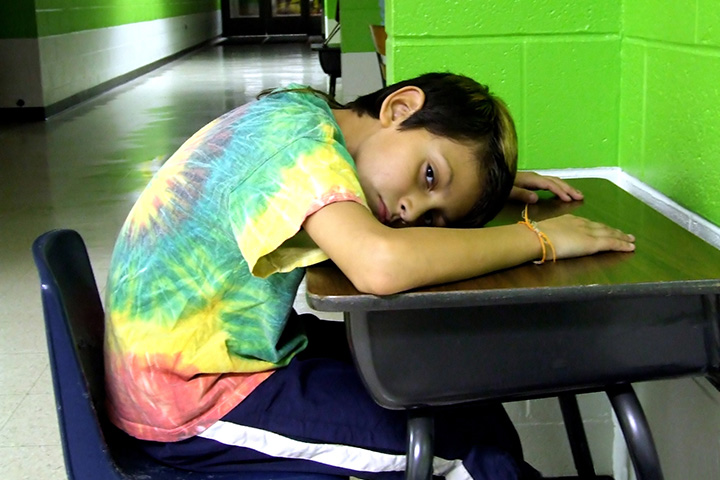

The Cobscook Community Learning Center launched its Transforming Rural Experience in Education (TREE) program this year at three elementary schools in Milbridge, Jonesport, and Charlotte, among the poorest areas of the state. Recent research in urban schools shows that students who experience trauma tend to struggle in school, and vast resources are dedicated to addressing the challenges arising from these struggles. But students in rural schools who experience similar trauma are often overlooked.

TREE’s efforts focus on helping poor rural students struggling with the same problems through a partnership with education researchers at Colby College and the University of Maine, and with the support of $1.3 million in foundation funding, the Bangor Daily News reports.

Laura Thomas, a former Milbridge Elementary teacher who now works as a coach for TREE, said the program starts with a simple question: “What are kids coming to school with besides just their backpacks?”

According to the Daily News:

The program isn’t just about poverty or drug addiction or hunger or special education or student performance or life expectancy. It’s about all of it. It’s about all the ways families and children in the area may fall on tough times, the trauma that causes, and the ways a school of 115 students can help kids overcome that trauma and learn.

TREE’s plan is to demonstrate through full-time coaches how schools can better respond to misbehaving students who may have experienced trauma, and improve academics by helping students work through their issues. The program is also working to help students access dental care.

The approach is one of many “trauma-informed” school initiatives based on recent research into how adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) impact health and brain development, behavior, and learning. ACEs include a wide range of experiences that lead to stress, from surviving or witnessing verbal, sexual, or physical abuse, to chronic hunger, traumatic divorces, or parents addicted to drugs or alcohol.

Research from the Center for Disease Control and Prevention and others suggest ACEs contribute to long term health problems including obesity and heart disease, and make it more likely for students to engage in risky behaviors.

Research shows students with at least three types of adverse childhood experiences are more likely than peers with less trauma in their past to experience depression, consider suicide, smoke cigarettes, and drink alcohol. The 2017 Maine Integrated Youth Health Survey revealed “31 percent of Washington County students recorded at least three adverse childhood experiences . . . the second highest rate among the state’s 16 counties.”

“When we think about all the challenges we’re having in education, how much of it goes back to ACEs and never having done anything that addresses that in schools?” TREE Director Brittany Ray questioned.

The trauma-informed approach has proved successful in improving student performance and decreasing conflicts and disciplinary problems by increasing mental health care in inner-city schools, and TREE officials are hoping for similar success in the rural settings.

“Most of the education reform work has been done in urban settings,” Colby College education professor Mikel Brown, a member of the TREE research team, told the Daily News. “Rural schools do not have the same access to everything, from nonprofit support to transportation.”

Richard Fournier, lead researcher of character formation in rural schools for the Institute for Advanced Studies in Culture’s recent School Cultures and Student Formation Project, pointed out in The Content of Their Character:

In general, rural school teachers and administrators face the same tasks as urban districts: to increase academic performance among students and prepare them for social and economic life despite their communities’ frequent issues with poverty, drugs, unemployment, and other socioeconomic obstacles. The schools’ tasks are difficult, and rural schools have unique features that both further and hinder these goals.

The work of TREE and similar organizations often doesn’t make the news because its focused in small towns, but it’s essential to the social fabric of rural communities that comprise more than nine million American students.

The Rural Schools Collaborative provides a place for rural educators with promising practices in this important sector of American education to share their experiences and help others along the way.