Hilderbrand Pelzer III once taught in a juvenile detention center. Now, as a principal, he says that student behavior in Philadelphia schools makes teaching harder than ever.

Pelzer quotes the principal of the Bensalem Youth Development Center School where he once worked: “It only takes one student to destroy and demoralize the learning environment.” In Philadelphia, officials estimate that more than half of all students have experienced a major traumatic event, according to the Philadelphia Citizen. With that many student needs, building and sustaining a thriving school climate can be a herculean effort.

Pelzer cites the Child Mind Institute, which says that about 10% of the school population nationally struggles with mental health problems. But only about one in three teachers think they have the skills to handle mental health issues.

Last year a group of teachers in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania’s state capital, shared stories of getting beaten up by students as young as six. Forty-five teachers resigned between July and October, 2017.

Pelzer writes: “A recent study from the University of Pennsylvania’s Consortium for Policy Research in Education found that teachers overwhelmingly think that suspensions helped them manage their classrooms.” In some schools, truancy has risen with the abolition of suspensions for minor infractions, and academic success among students not previously suspended has declined.

UCLA sociologist Jeffrey Guhin has observed similar patterns in urban public schools around the United States, though teachers are doing their best to connect with students and address the underlying issues. He writes in the Institute for Advanced Studies in Culture book The Content of Their Character that “there were often heroic commitments by teachers to show compassion to their students and to model such a compassionate life as a meaningful way to live.” Indeed, Pelzer and many others continue to make those heroic commitments, setting an example for their students.

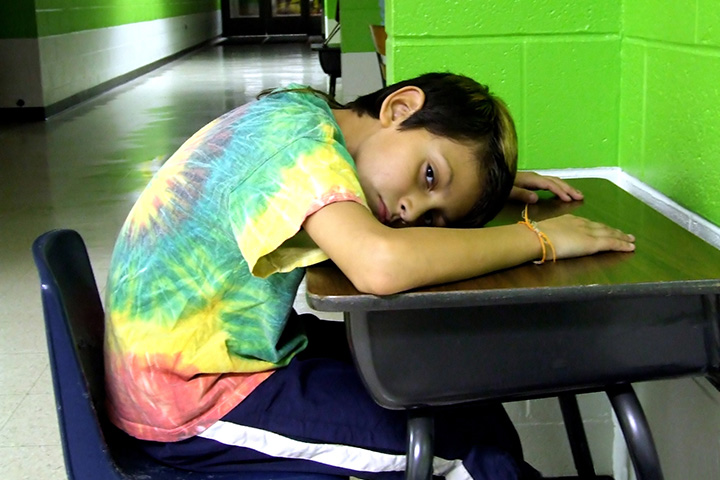

In Pelzer’s school, “distressed students struggle to follow basic instructions, and have difficulty focusing their attention on organizing, planning and completing tasks.” The burden falls on teachers, he says. “At my school, I’ve had parents tell me with relief as they drop off their children that it’s up to us to manage them for the day.”

Pelzer concludes: “It is increasingly clear that if we want more progressive disciplinary methods, we need one or both of two things: More in-school professional help, which can be costly, or better training.”

The International Institute for Restorative Practices addresses the training need through its degree, continuing education, and professional development offerings. There are no quick fixes, which makes the heroic perseverance of Pelzer and his colleagues all the more impressive.