I remember it was always on Wednesdays.

That’s when the all-purpose room in the basement of Marlowe Elementary transformed from cafeteria and gymnasium to art room. I couldn’t multiply two digit by three digit numbers. I was always picked last for the kickball team (“picked” meaning assigned a team because no 5th grader in their right mind was going to voluntarily choose the kid who would strike out in 30 seconds). My handwriting was horrendous, made worse as my left hand smeared my cursive attempts across the page.

Wednesdays were a different story – because I could draw. With colored pencils and paintbrushes at my disposal, I was a different person 45 minutes a week. Mrs. Altman, the art teacher, heaped on the praise when I finished my creations, and I believed every word of it. On Wednesdays, I’d brave the bullies at the back of the school bus, the social studies test I probably didn’t study for, and sitting by myself on the jungle gym at recess – because, for 45 minutes, I was the girl who draws. Art class gave me a sense of purpose.

Fast forward from 1993 to 2017. I went from the girl who draws to the teacher who draws. After a short stint as a communications major, I decided in college to switch to education because I wanted to be a part of people’s stories and successes instead of reporting on them. My aunt was a first grade teacher for 37 years, and memories of how she creatively reached her students – whether through Care Bears or Happy Meal toys – inspired me to make learning a fun, empowering experience, so kids would want to learn and feel they belonged in this crazy, upside down world.

For 17 years, I used many creative endeavors to fight against the increasing hyper focus on assessment, data collection, and progress monitoring in the elementary classroom. Slowly and steadily, each year I was losing myself, as it became next to impossible to be the teacher I wanted to be with the growing demands of test preparation. The worst part was what I saw it doing to my students – the ones with the bad handwriting, questionable study skills, or paddling against the current in math. Labels assigned to kids based on academic performance don’t show their talents outside of an 8.5 x 11 sheet of paper or clicked answers on a multiple choice test.

I felt as defeated as that fifth grader sitting on the jungle gym, until the last day of school 2017. As I packed up my classroom for the summer, I carefully took down my “refrigerator wall,” where my students hung drawings and knickknacks they made throughout the year. An illustration of a pencil versus a Sharpie, a pencil portrait of my cat Frankie, a sketch of a fighter jet – by the end of the year, the refrigerator wall was an eclectic mix of the talents and interests in my classroom.

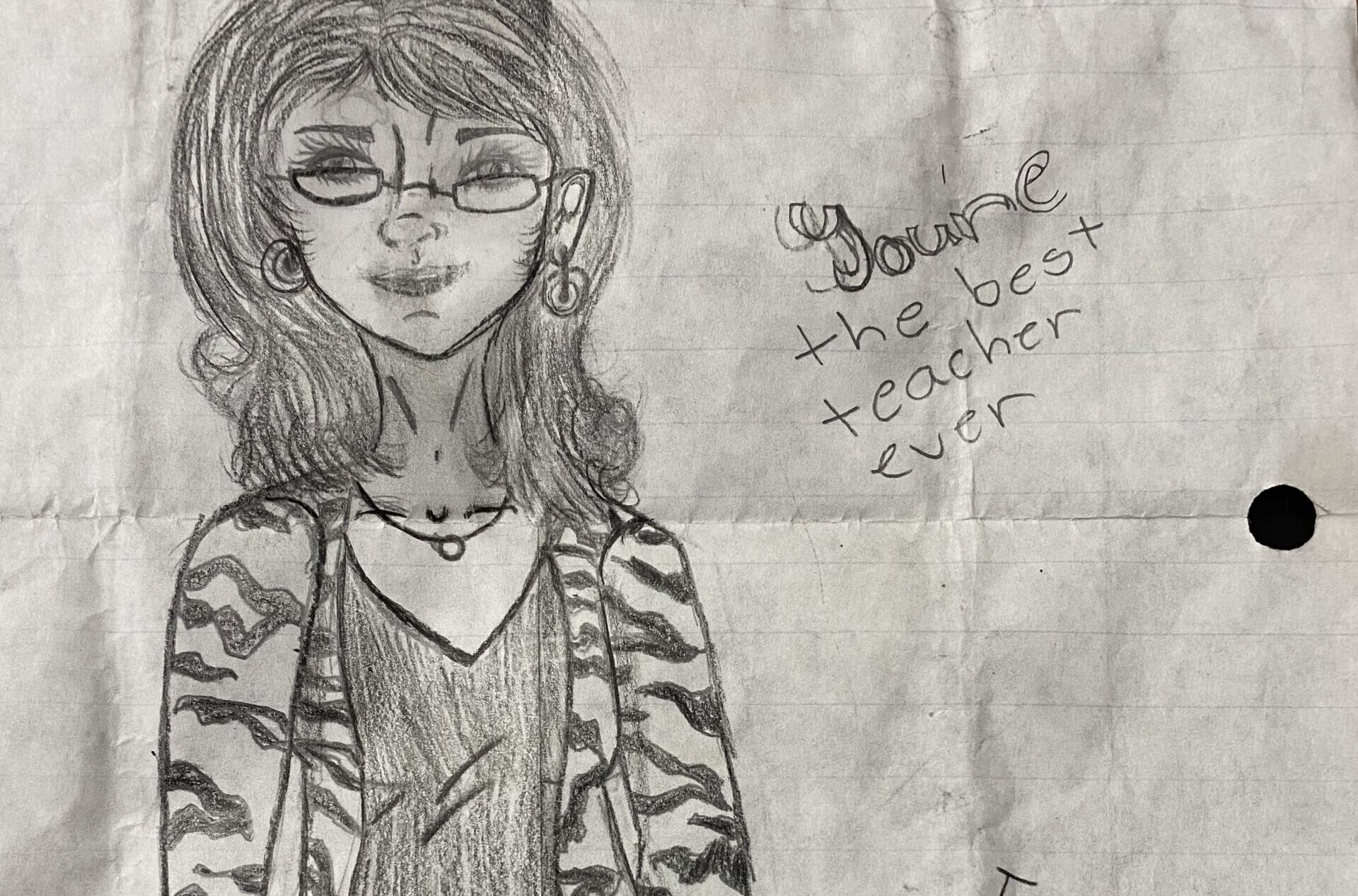

The last masterpiece I gingerly took down was a strikingly accurate portrait a student had drawn of myself – right down to the hair part and zebra print cardigan. The student who drew it was a lot like I had been in school – left out, left handed, and looking for a way to fit in the adolescent landscape.

In that moment I had no answers for the growing lack of creative autonomy in the general education classroom, but I did know my next step as an educator.

Where testing and skill recovery programs provide mixed solutions to increasing academic progress, art education consistently shows its ability to increase critical thinking and problem solving skills desired of students. The integration of all subjects allows for the reinforcement of the materials taught in the classroom, all while improving brain function through painting, cutting, weaving, and a multitude of other experiences. Memory building and fine and gross motor skills are developed through art in a way that worksheets can’t compete.

Every child has an invisible sign above their head that reads “Make me feel important.” Many children, especially those with special needs, get to experience a level of success and pride in the art room that won’t be replicated with test scores. The simple act of giving a child something to look forward to and the feeling of accomplishment from creating something out of nothing is a greater equalizer in education than any leveled reader or tiered instruction.

In the aftermath of COVID, we are not only addressing learning gaps but also profound grief. The emotional and social fallout from the pandemic is as great a crisis if not more than the impact on academic instruction. Kids are in as much need of stress relief and coping skills in this moment in time as they are skill building. In an art room, there is hope, peace, and healing intertwined with the joy of making something beautiful in the broken world. They don’t just learn to make art – they learn how to feel and heal.

We can do better in the post-pandemic era of education than we have in the past with an ever increasing reliance on statistical data to drive instruction. The creative, imaginative pursuits in the classroom will captivate student interest in learning and build the empathy needed for tomorrow’s leaders. It is my hope to bring that to eduction as an art teacher – so that every day feels like a Wednesday.

—

Erin Sponaugle is a National Board Certified Teacher, NNSTOY member, and children’s book author-illustrator. She has taught for 19 years and is the 2014 West Virginia Teacher of the Year. Erin currently teaches art at Tomahawk Intermediate School in Hedgesville, West Virginia. She is the host of the Next Chapter for Teachers Podcast, a show focused on teacher self-improvement. You can follow her on Twitter @erin_sponaugle, on Instagram @nextchapterpress, and read her blog at www.erinsponaugle.com