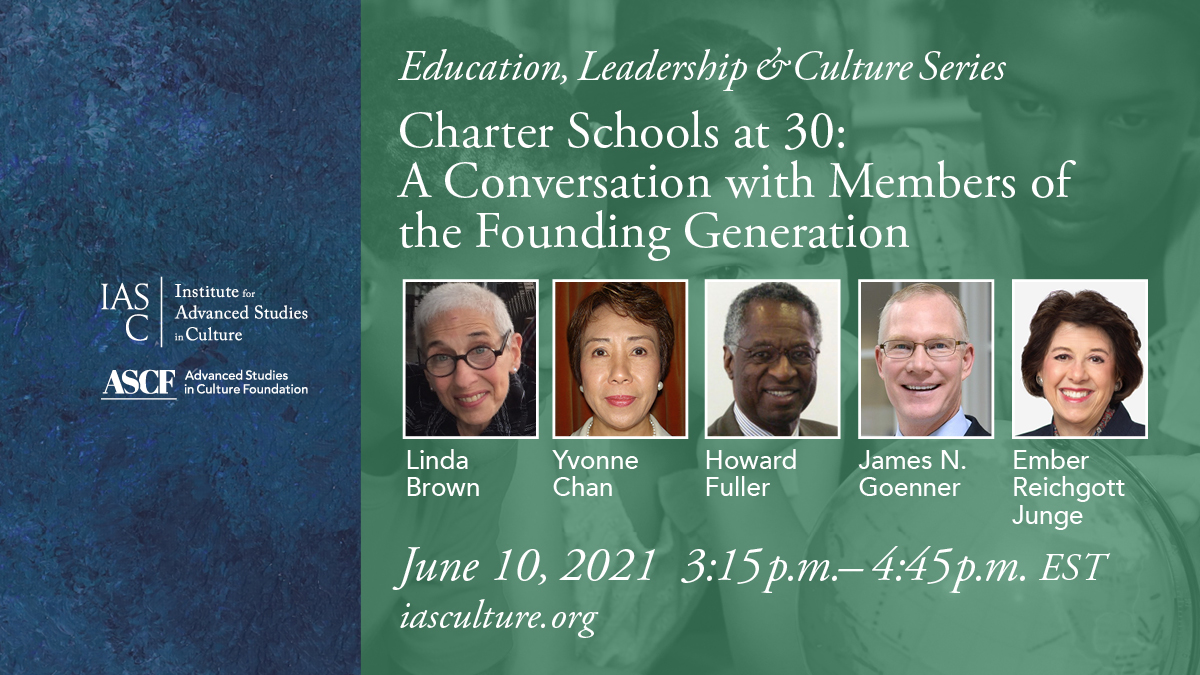

On June 10, 2021, five people joined me for a conversation about Charter Schools at 30: A Conversation with Members of the Founding Generation. My guests were Linda Brown, Founder of Building Excellent Schools; Yvonne Chan, Founder of the Vaughn Next Century Learning Center in Los Angeles, CA; Howard Fuller, Founder and Board Chair Emeritus of the Institute for the Transformation of Learning at Marquette University; James N. Goenner, President and CEO of the National Charter Schools Institute; and Ember Reichgott Junge, Former Minnesota State Senator and author of the nation’s First Charter School Law. Each panelist was invited to participate because he or she has rich experience working in the charter school profession.

Our dialogue centered around the 30th anniversary of the enactment of the first charter school law in Minnesota, as well as its challenges and triumphs. To gain insights into where we are today, let’s review data published by the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools to see how far charter schools have come since 1991 provided in the table below:

|

1991: Minnesota |

2021: 45 states plus the District of Columbia, Guam, and Puerto Rico (states without a charter law – Montana, Nebraska, North Dakota, South Dakota, and Vermont) |

|

1991: Fewer than 1,000 students |

2021: More than 3.3 million students |

|

1991: Fewer than 1,000 teachers |

2021: 219,000 teachers |

|

1991: Fewer than 100 schools |

2021: 7,500 charter schools and campuses |

Here are some other facts worth highlighting:

- 69% of all charter school students are students of color;

- 61% of all charter schools are freestanding (i.e., independent);

- 29% of all charter schools are managed by a nonprofit network; and 11% of all charter schools are managed by a profit organization;

- 59% of all charter school students receive free or reduced priced lunch; and

- 58% of all charter schools are located in an urban area;

- 30% are in the suburbs; and 12% are in rural areas or towns.

Here are some of the questions that I asked of each panelist:

Ember Reichgott Junge: You worked on education issues before, during, and after your time in the Minnesota legislature. Your state became the first in the nation to enact a charter school law, and your role in that work was essential. Why did you pursue a charter school law? Why was the time ripe for this type of reform? Who was on board? Who was not?

Yvonne Chan: California is the second state in the nation to enact a charter school law, and you opened one of the first charter school in Los Angeles. Tell us about the “ah ha” moment when you decided to open the Vaughn Next Century Learning Center. What were the early wins you experienced? What where the early challenges you experienced?

James N. Goenner: You have played a leadership role in nonprofit organizations that advance charter schools, be it in Michigan or nationally. What attracted you to charter schools in the first place? How has your organization moved the charter school conversation with lawmakers, advocates and the business community? What is the most important issue facing leaders of nonprofit charter organizations (other than money)?

Linda Brown: You work in Massachusetts, one of the early charter school states. Your contribution to charter schools is through building boards to produce excellent schools. Why did you take this approach? What are some of the successes and challenges you’ve seen over the years as it relates to board members and charter school leadership or governance?

Howard Fuller: You are a former superintendent of Milwaukee Public Schools who used that experience to lay the foundation for charter schools to gain ground in that city. At the national level, your work with the National Alliance for Public Charter School and BAEO did the same. Given your focus on the role of black people (and others) in the charter school movement, what have we done well? Where do we have room for growth? How is your charter school in Milwaukee playing a role to advance academic and leadership opportunities for black students and adults?

Group Question: Charter schools have provided numerous academic, social, and economic benefits to children, educators, families, and the communities that they call home. At the same time, charter schools are under attack—by some former friends as well as the usual suspects. Knowing what you do today with 30 years of experience and hindsight, what should the current generation of charter school founders, educators, board members, nonprofit leaders, philanthropists, and charter alumni do to ensure charter schools are alive and well for another 30 years?

To watch or listen to this informative conversation, click here: https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=p7awzx93kN4&feature=youtu.be