A literate life? What does that mean? Perhaps at its most basic, it means having enough knowledge to do what you need to do. If you are using a computer, a certain level of computer literacy is needed. But what does it mean in the realm of reading and writing? What does it mean to be literate in these areas?

As a fan of the Little House on the Prairie Series, I often think of literacy as it is presented in the many episodes. Students are seen practicing their spelling on the board or reading from a basal reader to the whole class. Oftentimes, they are writing to a whole class prompt. They’re growing their literacy. But our world is changing. The areas in which students needs to be literate need to change as well. The information coming to them has multiplied through many different sources, such as Facebook, Instagram, Tiktok, etc. These sources bombard our students with information.

But have our students learned to think critically about the information that is coming to them? Have we prepared our students to be critical consumers and to evaluate what they see before assuming it is correct or accurate? Young learners need to be more critical purveyors of knowledge. They no longer can assume that what they’re reading is truth. They must decipher, from multiple sources, what is accurate and inaccurate – a task most adults find difficult to do.

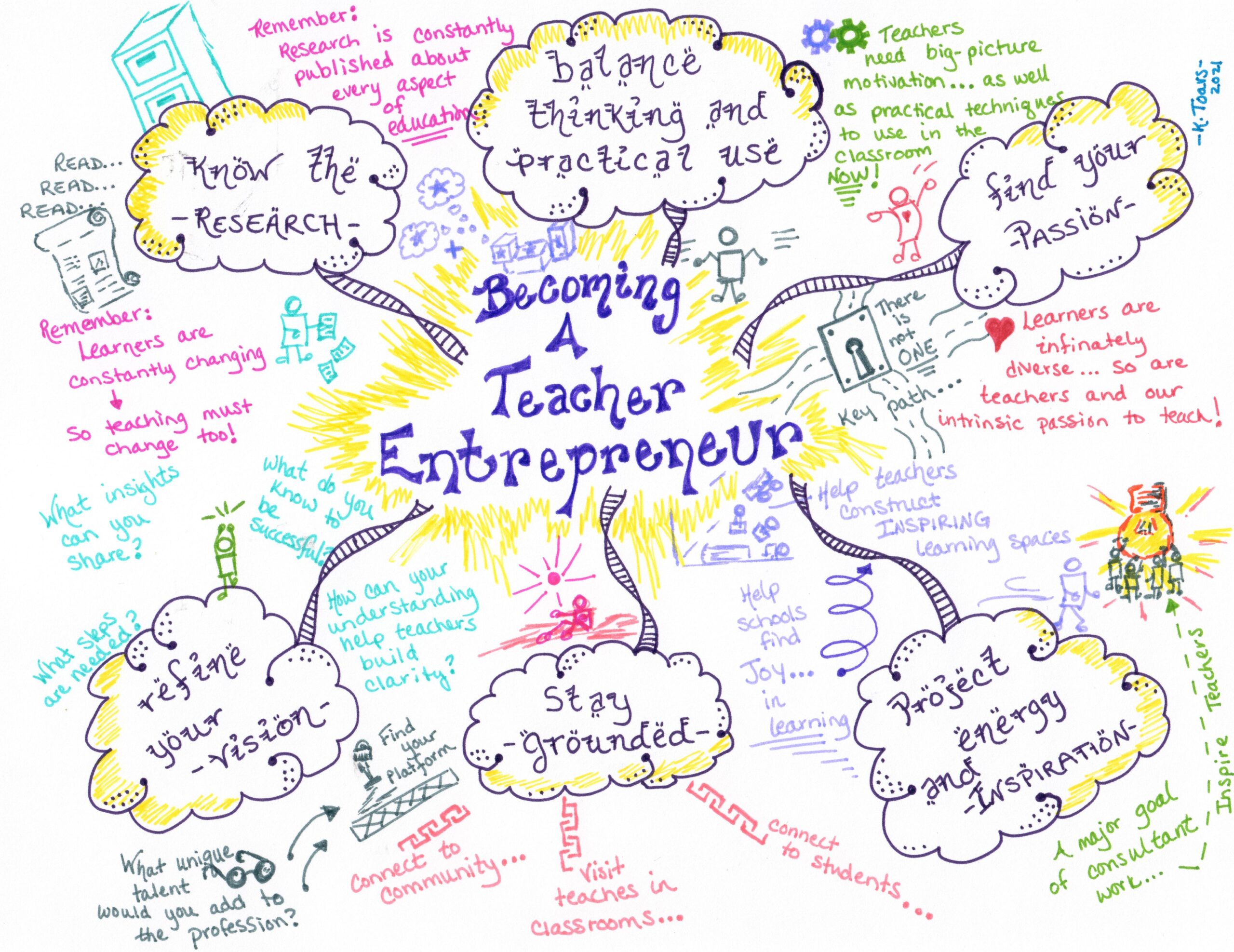

So, what does it mean to be literate as a 21st century learner? It is critical to teach foundational skills, to not make light of their importance. These skills are necessary in today’s society. But armed with those skills alone, our young scholars will not be able to effectively critique what they have written and read and consider multiple sources that may present varying perspectives.

This author would argue that young people need to understand that there will be conflict. But what should happen at that juncture? Literature serves as a context for helping students view the world either as a mirror or window. Emily Style, who works for the National SEED Project, describes a mirror as a story that reflects your own culture and helps you build your identity. A window is a resource that offers you a view into someone else’s experience. It is critical to understand that students cannot truly learn about themselves unless they learn about others as well. It involves reflection.

Chimamanda Adichie, in the Ted Talk “Danger of a Single Story”, explains the importance of providing a window for students using the context of literature to help them see multiple perspectives on any given topic. In other words, give students the experience of many stories. Literature teaches about tolerance, to learn about someone else’s experiences, and why they hold the perspectives that they do. It teaches open-mindedness to understand that perspectives come from sets of experiences and that the more experiences gained, the more likely we are to accept others for their differences. This allows celebrating others for their differences and does not allow limited understanding to cause misunderstanding.

Another literacy to consider is ethical literacy. This does not mean imposing educator ethics on students. It means teaching students to use what they understand about perspectives and apply this knowledge to situations in which core values conflict. This empowers learners to participate and initiate change in a global society.

Literacy is a simple word, but its meaning is complex. Jess Lifshitz, during her Innovative Education in Vermont podcast, shares her understanding of the seminal text by Dr. Gholdy Muhammad, Cultivating Genius: An Equity Framework for Culturally and Historically Responsive Literacy. In reference to literary skills she quotes, “That we can’t teach these isolated skills to kids and then expect kids to go out into the world and make the kind of changes that we know are needed. And that we hope for them to make.” The challenge for educators is to use literacy and literature to give students many opportunities to look in the mirror and out of the window to create intelligent, critical thinking citizens.

—

Laura Drake is a Wyoming native of 55 years. She has been in education for 32 years teaching K-6 Regular and Special Education, as well as serving as an instructional coach. Drake has a master’s degree in literacy, is a National Board Certified Teacher (with renewal), the 2013 Wyoming Teacher of the Year, and has her Ed.D. in Curriculum, Instruction, and Assessment. She is now retired and is pursuing her cake decorating business, as well as doing peer review work for our department of education. She also aspires to teach at the collegiate level.