Sugar Todd is a highly decorated speed skater who competed for the United States at the 2014 Olympics. Reaching these heights of athletic accomplishment can seem daunting, but Todd is demystifying her success by working with Classroom Champions, and helping 2nd-grade students see that it’s built on a foundation of character and hard work.

Todd was paired with the group of 2nd-graders in Racine, WI, through Classroom Champions. The 74 profiled the organization to learn more about its founder, their mission, and the work being done to help students across the country.

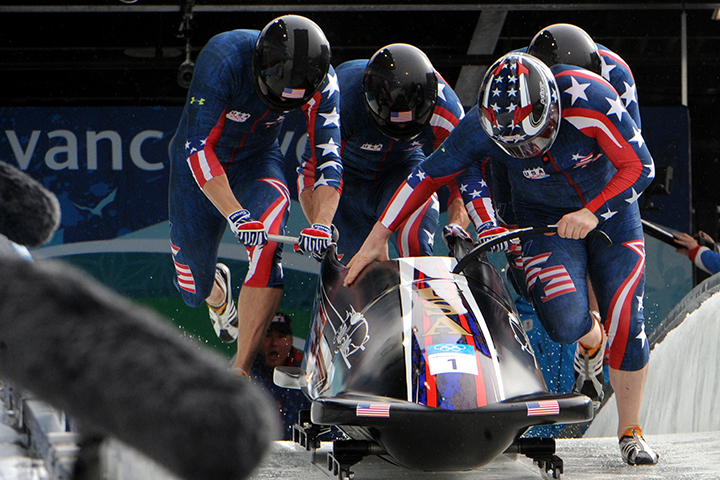

Steve Mesler, a former Olympic bobsledder who won gold at the 2010 Games, started Classroom Champions. He told The 74 that the original idea behind the nonprofit came from his own work with schools and Fortune 500 companies. The companies brought him in to talk about “overcoming failure, determination, goal-setting,” but in schools he mostly found himself addressing more basic topics like “healthy living.”

Mesler knew that he, and other elite athletes like him, had more to offer to students. These current and former athletes are clear manifestations of the results of dedication and perseverance, but they also have lessons to offer about sportsmanship and respect.

So, he founded Classroom Champions with the goal of connecting elite athletes and students in mentoring relationships. The organization would utilize new technology to facilitate large numbers of these interactions across the country and globe.

The athletes, like Todd, are matched with several different classrooms. According to The 74, they then “[M]ake monthly videos on topics like fair play, determination, and community that they share with the students. Once a week, teachers present lessons on these skills, and [teachers] incorporate social-emotional vocabulary words such as grit, perseverance, and determination throughout the school day.”

Todd’s students in Racine, and their classroom teacher, were particularly moved by her words following her failure to qualify for the Pyeongchang Games. As she said, “I was ready. I was capable. I was going to crush. But I didn’t. And the heartbreak that followed stunned me.” She was at the lowest point an athlete can be, but she still inspired the 2nd-graders by congratulating the skater who took her place on the Olympic Team.

She said of someone else living her dream: “I can celebrate that.” It is remarkable that Todd, who invested countless hours and boundless energy into a goal that eventually disappeared, still displayed kindness and sportsmanship in losing.

Classroom teacher Amy Simon even admitted that Todd’s lessons on perseverance had an impact on the challenges she faces as an educator.

This is a reminder that forming character traits like determination, grit, and good sportsmanship is the work of a lifetime. Having supportive adult role models—such as admired elite athletes—is important for children and adults alike.

“There is considerable evidence that strong social support contributes crucially to academic success in school, whether that support comes from parents and family, youth organizations, or religious communities,” write James Davison Hunter and Ryan S. Olson in the conclusion of The Content of Their Character, which contains the research findings of the School Cultures and Student Formation Project of the Institute for Advanced Studies in Culture.

Classroom Champions founder Steve Mesler said, “These kids identify with the athletes in such a powerful way, it changes the way they treat each other.” At the end of the day, that’s even more important than their improved perseverance and determination.

Check out how you can bring Classroom Champions to your classroom.