The images are first chilling and then touching—a large gun, and then a long embrace.

The surveillance video released last weekend has been viewed hundreds of thousands of times. It shows a scene from May in which Keanon Lowe, a security guard and football coach at Parkrose High School, took a loaded shotgun from then-18-year-old Angel Granados-Diaz and then wrapped him in a hug.

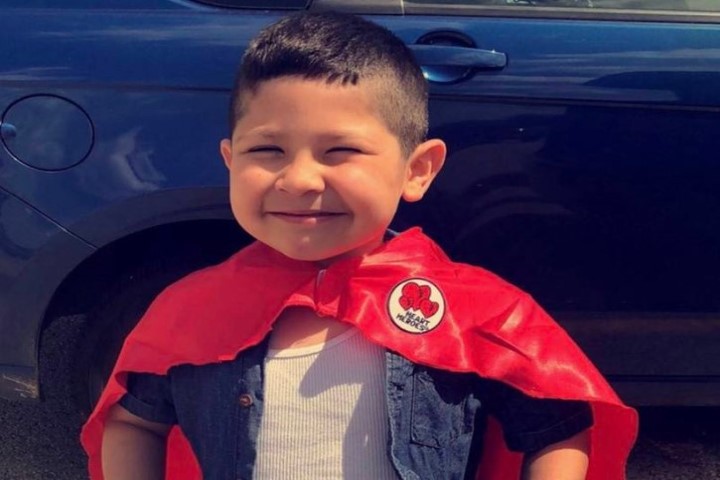

Granados-Diaz planned to kill himself that day—at school rather than at home so that his mother would not find his body. Lowe, having heard about “suicidal statements” made by Granados-Diaz, showed up in the student’s classroom right before Granados-Diaz arrived, carrying the gun under a long coat. Granados-Diaz tried to fire the gun on himself, but it did not discharge.

“I saw the look in his face, look in his eyes, looked at the gun, realized it was a real gun, and then my instincts just took over,” Lowe said. “I lunged for the gun, put two hands on the gun.”

As the recently released video shows, Lowe removed the gun from Granados-Diaz and handed it off to another teacher nearby. Lowe then wrapped his arms around the student, who began to cry. For a few moments, Granados-Diaz struggled against the embrace of Lowe, but then returned it.

In those moments, said Lowe, they had a conversation.

“Obviously, he broke down and I just wanted to let him know that I was there for him,” Lowe said. “I told him I was there to save him—I was there for a reason and that this is a life worth living.”

Lowe’s response is a striking model of character in at least two way. First, he showed the courage to act without thought for his own safety. Concerned for the well-being of Granados-Diaz and the other students, Lowe deliberately put himself in harm’s way for their sake.

And then, rather than responding with force and censure—which would have been understandable given the degree of risk Lowe had just faced—Lowe extended compassion and care. Granados-Diaz would later receive legal penalties associated with weapons possession, but in this vulnerable moment, Lowe led with love.

Every teacher interacting with a student who is breaking the rules faces this same double crossroad. Will we have the courage to confront the misbehavior—to call it out, to disarm it—for the child’s sake and others’? And at the same time, will we have the compassion to see beyond disturbing conduct and embrace the student who acts out from a place of pain? To keep showing love even when a child tries to push us away?

Lowe would not have been a good security guard had he failed to act on the threat; it is not loving to ignore destructive behavior. At the same time, the life of Granados-Diaz might be radically different had Lowe not responded with powerful, inescapable kindness.

Students are watching the educators around them. They imitate the way we treat our colleagues—and also the way we respond to those who act out. May we model both courage and compassion as we engage the often-hurting students around us.