Daniel Warner was drawn to the profession of teaching by the opportunity to cultivate thinkers and learners. Now, his students are engaged in vigorous debates drawing on primary sources.

Chalkbeat interviewed Warner to learn more about his background, classroom practices, and the connections he tries to make between history and contemporary society.

Before he was leading students on explorations down the path of American history, Warner was a college student who hadn’t even considered a career in teaching. During his senior year he learned about an alternative certification program that would allow him to become a teacher directly after graduation. He relished the opportunity to have an immediate impact.

While there are portions of any U.S. History course that can be tedious, “The teacher has to keep it upbeat when it’s the third day in a row on the issues of 19th-century farmers,” he jokes. There are also themes that are just as applicable today as they were 140 years ago.

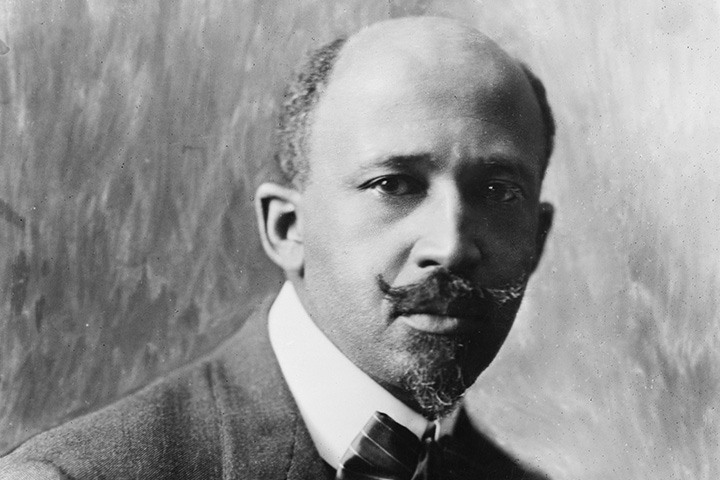

In particular, Warner requires his students to read Booker T. Washington’s “Atlanta Exposition Address” and W.E.B. DuBois’ “Talented Tenth.” Warner says, “At the end of the week, we have a rigorous classroom debate in which students have to quote from the primary sources to defend their positions.”

Warner finds that as a result of comparing and contrasting the ideologies of these two different leaders, students develop personal connections with the historical thinkers. Ultimately, this should be the goal of any social studies educator: to show students that a historical understanding of the world can help them to build their own contemporary views of society.

Warner also finds it beneficial to try and tie classroom instruction to the interests of individual students. Through this, he signals to them that they matter to him as more than students—their own passions and interests are reflected in the choices he makes about curriculum.

“How a school is organized, the course structure and classroom practices, the relationship between the school and outside civic institutions—all of these matter in the moral and civic formation of the child,” write James Davison Hunter and Ryan S. Olson, the editors of The Content of Their Character, a recent publication from the Institute for Advanced Studies in Culture.

“Each year, students walk away empowered to connect their stories with the ones of those who have gone before them. History class becomes worth their time,” reflects Warner.

But there’s something even more fundamental in Warner’s classroom practices—caring for his students as persons. He says, “I heard James Baldwin say that Malcolm X was so adored by his followers and stirred them to action because he made them ‘feel as though they truly exist.'”

Warner’s students seem to feel that same deep affirmation.

The Library of Congress has suggestions for teaching Booker T. Washington’s “Atlanta Exposition Address” for educators looking to follow Warner’s example.