Teachers are no strangers to heavy lifting. They support one another in challenging times, and they shoulder the burdens of their students on a daily basis. For one Ohio teacher, carrying a student became literal.

Ten-year-old Ryan King is accustomed to missing out on activities. Born with spina bifida, she is confined to a wheelchair. When her class field trip to a fossil bed by a river was recently announced, Ryan hoped she could go, but her mother was dubious. The fossil bed isn’t wheelchair accessible, and the only alternative was to carry her.

Just like other preteens, Molly craves adventure and independence from her mom—two things that were in short supply. This field trip was another reminder of her limitations.

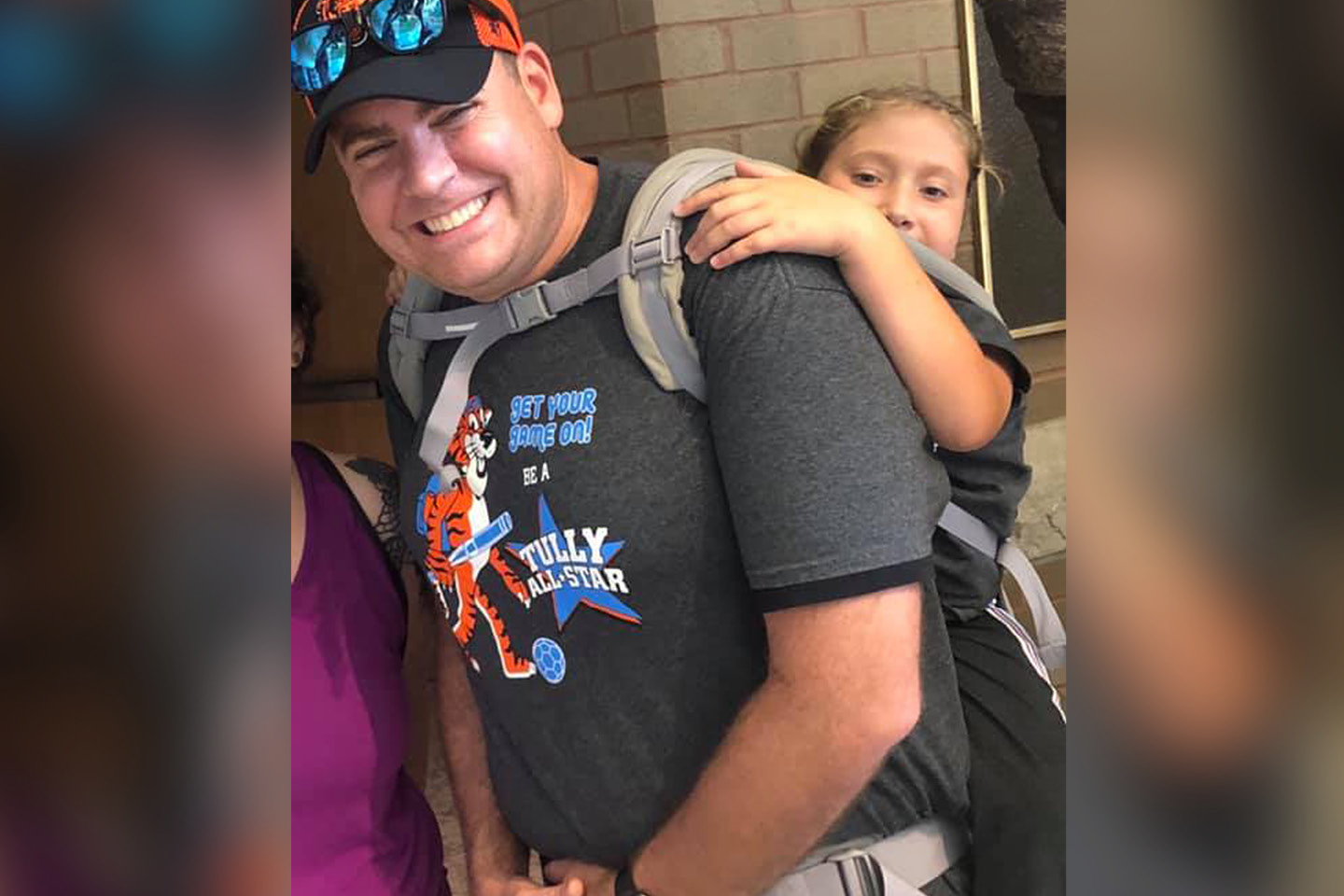

In stepped teacher Jim Freeman, a teacher at Molly’s school. Freeman doesn’t oversee her class, but he was familiar with her smile from the hallway. For an hour, Freeman carried the 50-pound girl in a backpack carrier in 90-degree heat. Ryan had a wonderful time and was happy that for once, her classmates envied her.

“A little time out of my day and a little extra effort can give Ryan something to remember,” Freeman told Good Morning America.

Freeman well sums up the cost of serving another—in so many cases, it’s just a little time and a little extra effort. Call it what you will—kindness, compassion, generosity—this trait has the potential to radically change the experience of another person.

Extra time and effort is something most teachers provide almost instinctively. They give haircuts before fifth-grade graduations; they read to their students in the evenings on Facebook Live. And students benefit. But what if, beyond receiving a new haircut, a boost in literacy, or a piggyback ride over rough terrain, students are also receiving something even more powerful? What if the behavior they see impacts the people they become?

In the book The Content of Their Character, James Davison Hunter and Ryan S. Olson call this phenomenon “catching.” Values and behavior are contagious. As teachers model character, the students in their lives mirror it.

Consider the story of Sophia Alvarado. Melody Harbour, a special education teacher’s aide at Sophia’s school, was recently diagnosed with stage three lung cancer. According to KCBD-TV in Lubbock, Texas, Harbour endured 30 rounds of radiation and four rounds of chemotherapy. When Sophia, a third grader, saw that Harbour’s hair had fallen out, she decided to cut off her own hair in solidarity.

“This little girl is why I have to do this every day. There’s a lot of them in there,” Harbour told KCBD-TV, pointing at the school. “I can’t just sit at home and dwell on my problems.”

It’s clear that Sophia, with her gift to Harbour, chose to focus on the needs of others as well.

In another recent situation, a teacher’s asthma attack was averted by the care and quick thinking of a student. Ten-year-old Nevaeh Woods was volunteering in Kim Rosby’s kindergarten classroom when Rosby was suddenly struggling to breathe and unable to speak. Rosby held up her car keys to indicate that her inhaler was in her locked car; Woods responded by seizing the keys and running to retrieve it. Her quick thinking saved Rosby’s life.

So accustomed are they to giving, teachers don’t expect to be recipients of students’ consideration. But the experience is sweet. Beyond the actual benefit is the knowledge that one’s own example may have contributed to the child’s action.

A child’s instinct toward kindness is either reinforced or undermined by the messages and examples around her. And the teachers who “carry” their students—both literally and figuratively—are helping shape “carriers” without saying a thing. Some children won’t bear the burdens of others until adulthood, but some will bear burdens now—sometimes even those of adults.