Students at Liverpool, New York’s Morgan Road Elementary School spend about 15 minutes a day learning about character, and how to become positive people. “We spend hours on (English and language arts),” principal Brett Woodcock told WRVO. “We spend hours on math. We spend a significant time on science and social studies. But this might be the most important thing we do.”

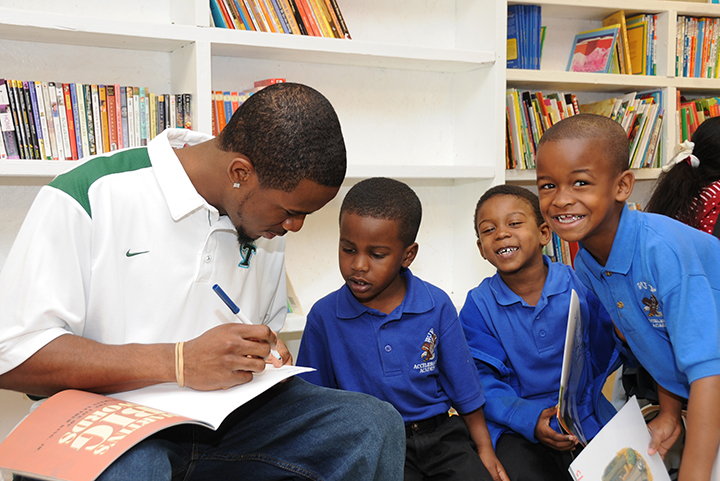

Morgan Road students joined The Positivity Project two years ago as part of an effort to teach children to be positive people, and a recent $24,000 grant from the Central New York Community Foundation will expand the program to 44 schools throughout the region this year. The Positivity Project, started by two former U.S. Army war veterans, focuses on two dozen character strengths identified by scientists, and encourages students to reflect on their own strengths and weaknesses.

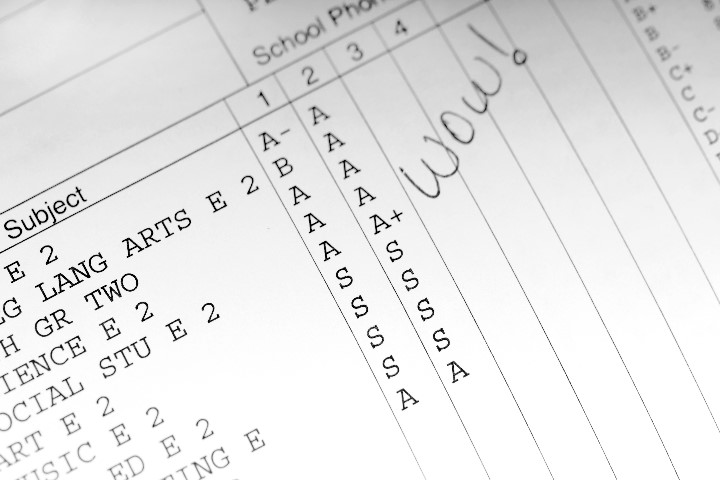

Fourth-grader Makenna Metrick told the news site her best strengths are “perseverance, bravery and kindness,” while her weaknesses include “appreciation of beauty and excellence, humility and modesty, and creativity.” “They have a better understanding of who they truly are,” Woodstock said. “And when it comes to situations of bullying and things like that, really having that self confidence and self awareness is a key piece of that.”

According to The Positivity Project website:

Each school and every classroom is different. Instead of a mandatory pedagogy and curriculum, we trust educators in the classroom–who know their students best–to implement P2 in the most impactful way possible. Empowering teachers to master the 24 character strengths language and concepts–and equipping them with resources–drives success in classrooms and schools.

Since its first partnership with Morgan Road elementary in 2015, The Positivity Project expanded to 33 schools in 11 states in 2016, and is now in place at 188 schools in 13 states—engaging 14,219 educators and 115,725 students. The growing popularity of the program represents an important shift away from an exclusively academic focus in schools to a more holistic approach that introduces children to the language of character at a critical time.

The trend also raises concerns about unintentionally reinforcing self-actualization as a primary goal, rather than a desire for students to look beyond themselves. UCLA sociologist Jeffrey Guhin highlighted that issue in recent research of urban public schools.

“Yet in the absence of a stronger ethical sensibility that could carry throughout the school and community, students were left to find larger ethical visions that might work for them. For some, that vision was a kind of materialist self-advancement, yet for many it was a sense of self-actualization, a need to ‘be yourself,’ whatever that ‘self’ might be,” Guhin wrote in the new book The Content of Their Character, set for publication next month by the Institute for Advanced Studies in Culture. “To the extent students were committed to altruism, solidarity, or broader public virtues, it was always through this diffuse institution of individualism, of insisting that what you most owe the world is your own self-realization.”

Fortunately, at Morgan Road Elementary, students like Makenna seem to understand the bigger picture. The 4th-grader said The Positivity Project has helped her better understand her own world, and how she can help those who need it, WROV reports. “Like if someone’s not treating their friend nicely, I’ll be like, ‘Don’t do that, you shouldn’t do that at all,’” she said. “And they’ll be like ‘Okay, Makenna, I won’t.’”

Guhin’s research represents one of ten sectors of education analyzed in The Content of Their Character, which is currently available at a discount through CultureFeed. Teachers can find more information about The Positivity Project, including training opportunities, on the organization’s website.