New Hampshire principal Brian Stack is offering his insight on teaching students “soft skills” through his own experience helping his elementary-age sons with their nightly homework.

In a MultiBriefs Exclusive column, Stack detailed how his 11-year-old son often struggles with challenging assignments and shuts down, while his 9-year-old learned to persevere through academic adversity with the help of his 3rd-grade teacher.

The coping strategies for working through tough assignments “have been specifically taught to him by his third-grade teacher over the past year as a concerted effort to focus on the development of learning skills, also known as soft skills, alongside academic standards and competencies,” he wrote.

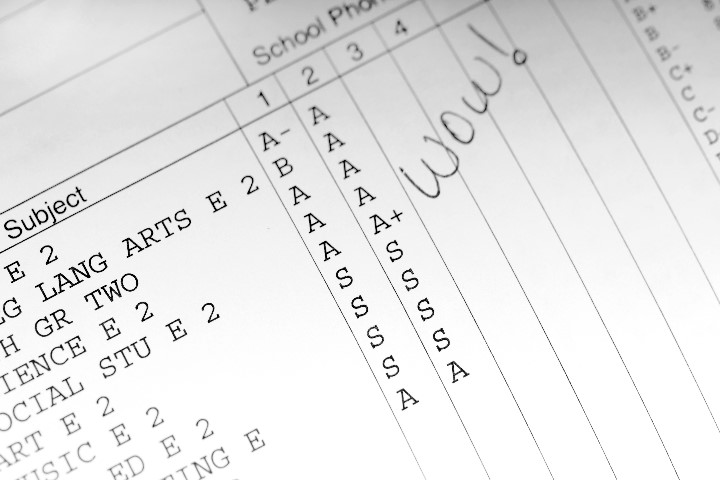

“For many schools, my kids’ elementary school included, the next iteration of this work is to include soft skill grades on report cards.”

The focus on helping students develop “soft skills” like perseverance or “grit,” is nothing new in the education world, but assessing and grading students on those skills remains largely uncharted territory.

Stack contends that developing measures and grades for students’ soft skills could help employers better understand whether applicants possess the intangibles needed for the job, and he pointed to several schools that already grade students’ noncognitive skills.

“In a recent article for Education Week, author Evie Blad reported on a Montgomery County, Maryland, elementary report card that reports on soft skills like intellectual risk-taking, collaboration, originality, and metacognition (the awareness of one’s own learning processes),” Stack wrote.

“Similarly, elementary report cards in Austin, Texas, chart how well students take responsibility for their own actions, manage their emotions constructively, and interacts with peers and adults. Blad went on to suggest that the biggest challenge for schools looking to add soft skills to their report cards is to figure out how to present the information in a meaningful and useful way for both students and parents.”

Stack noted that many researchers have warned against attempts to measure soft skills, but argued that “if the primary purpose of schooling is to prepare children to be successful in the workplace, then it is a logical step for schools to be more explicit about the teaching of soft skills.”

The rising interest in soft skills offers an opportunity for educators who entered the profession because of their passion for learning and formation—not for test scores. Adding soft skills to report cards, though well-intentioned, may only increase the current obsession with grades.

Some also argue it’s a bad idea because current measures are unreliable.

Education researcher Jeff Dill and Dan Scoggin, co-founder of Great Hearts Academies charter schools, penned a column for The Hedgehog Reviewa publication of the Institute for Advanced Studies in Culture, that points to comments from Angela Duckworth, a University of Pennsylvania professor who coined the term “grit” as an important academic virtue.

“(A)s psychologist Angela Duckworth notes, current measures for non-cognitive outcomes are limited by self-reporting and reference bias,” Dill and Scoggin wrote in THR. “Adding character to the testing regime at this state would be premature and counterproductive.”

Dill and Scoggin also argue that many schools rightfully pursue a vision that’s much greater than simply preparing students for the work world.

“(W)e can all agree that every school, embedded rightly within its community and context, needs a North Star of human flourishing,” they wrote. “Just as a good teacher has a clear objective for every lesson and course, just as a good school unites students and teachers around an intentional curriculum and program, so a great school must have a vision for the nature of the human being they seek to graduate.”

With clarity and purpose, great schools explicitly nurture not only soft skills, bot other dimensions of character, as well.

In a video about Scoggin’s Great Hearts Academies, he explains that “education is not just about getting kids into college or just about learning specific skills.” At Great Hearts’ network of classical charter schools, educators are committed to helping each student become a “better, more well-rounded and thoughtful human being.” Resources from the Jubilee Centre for Character & Virtues can help teachers work with students to develop the virtues necessary for human flourishing.